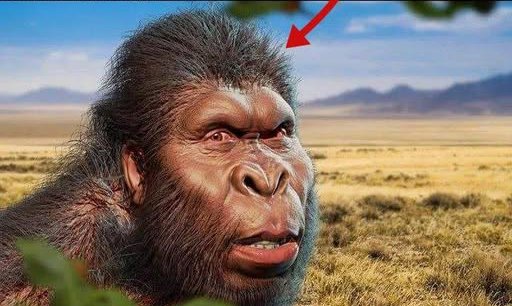

A New Genetic Frontier in Human Evolution

Hominins—humans and their ancient relatives—first emerged in Africa around seven million years ago. In a groundbreaking study, scientists have retrieved genetic information from Paranthropus robustus, a robust hominin species that lived two million years ago in South Africa, marking the oldest molecular data ever recovered from a human relative. The protein sequences, extracted from fossilized teeth found in Swartkrans Cave near Johannesburg, were analyzed using mass spectrometry. Researchers identified roughly 400 amino acids in enamel proteins, including amelogenin-Y—a marker of male sex—on two samples, overturning previous assumptions about one fossil’s sex based solely on tooth size.

Unlike DNA, which rapidly degrades in warm climates, proteins are more durable, enabling researchers to reconstruct limited evolutionary relationships where genetic material was long believed to be lost. The findings confirm that Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, and Denisovans are more closely related to each other than to Paranthropus, aligning with prior fossil-based models. Sequence differences in enamel proteins among the teeth also suggest internal variation within the species.

This pioneering use of ancient proteins, or paleoproteomics, opens new avenues in understanding early hominin biology, particularly when bones are fragmentary or DNA is unavailable. However, experts caution that enamel proteins offer limited variability compared to DNA, and the evolutionary trees derived from them lack the resolution of earlier genetic studies. Nonetheless, researchers view the ability to determine sex and species diversity from highly degraded remains as a potentially transformative tool in paleoanthropology. As the field matures, ethical concerns about destructive sampling are driving the development of non-invasive methods to screen fossils, balancing scientific discovery with preservation.