Elite Woman with Elongated Skull and Gem Teeth Found in Ancient Mexico

Archaeologists Discover 1,600-Year-Old Woman with Elongated Skull and Gem-Encrusted Teeth in Mexico

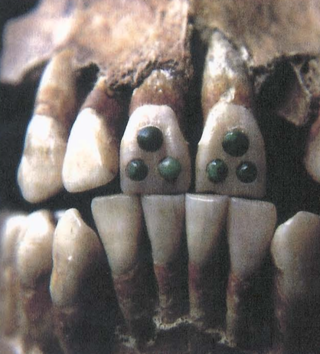

Archaeologists in Mexico have unearthed the 1,600-year-old skeleton of a woman whose features suggest she belonged to the upper class of her society. The remains, found in the ancient city of Teotihuacan, revealed an intentionally elongated skull and teeth encrusted with minerals—features that are both rare and striking.

While cranial deformation is not uncommon in archaeological finds, researchers described this case as one of the most extreme examples ever recorded. “Her skull had been intentionally elongated through severe compression, a technique typically seen in southern Mesoamerica, not in the central region where she was discovered,” the team stated, according to a report from AFP.

The skeleton was found by researchers from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) in the area known as Tlailotlacan, a district within the ancient city. The woman has since been dubbed The Woman of Tlailotlacan.

What sets her apart even further are the pyrite stones—shiny minerals resembling gold—embedded in her upper teeth, as well as a lower tooth made from serpentine. These modifications, particularly the use of exotic materials, suggest she may not have been native to Teotihuacan, and may have originated from a different region entirely.

While the team has not explained exactly how these dramatic body modifications were carried out 1,600 years ago, similar practices in other Mesoamerican cultures, such as the Maya, suggest that cranial shaping was typically done during infancy using bindings, likely to signify social status.

Interestingly, this isn’t the first time archaeologists have uncovered gem-studded teeth in ancient remains. In 2009, a different group of researchers found 2,500-year-old Native American skeletons with similar dental adornments. Those studies suggested the modifications were largely decorative and not necessarily indicative of class, and that the procedures involved surprisingly advanced dental techniques—possibly even the use of herbal anesthetics.

José Concepción Jiménez, a member of the INAH team, told National Geographic that some form of plant-based pain relief may have been applied during the drilling process.

It’s worth noting that these new findings have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal, so the interpretations should be viewed as preliminary until further research is released.

This discovery adds to a growing list of remarkable archaeological finds around the world. In June, Australian researchers uncovered 700,000-year-old hominin remains—nicknamed “hobbits”—on an island in Indonesia. And just last week, scientists in China reported what might be a skull fragment of the Buddha, discovered inside a 1,000-year-old shrine in Nanjing.

Clearly, it’s been a busy and exciting year for archaeologists—and the ancient world continues to reveal its secrets.