The Fortress of Dead Sheep: Ancient Stronghold of Khorezm

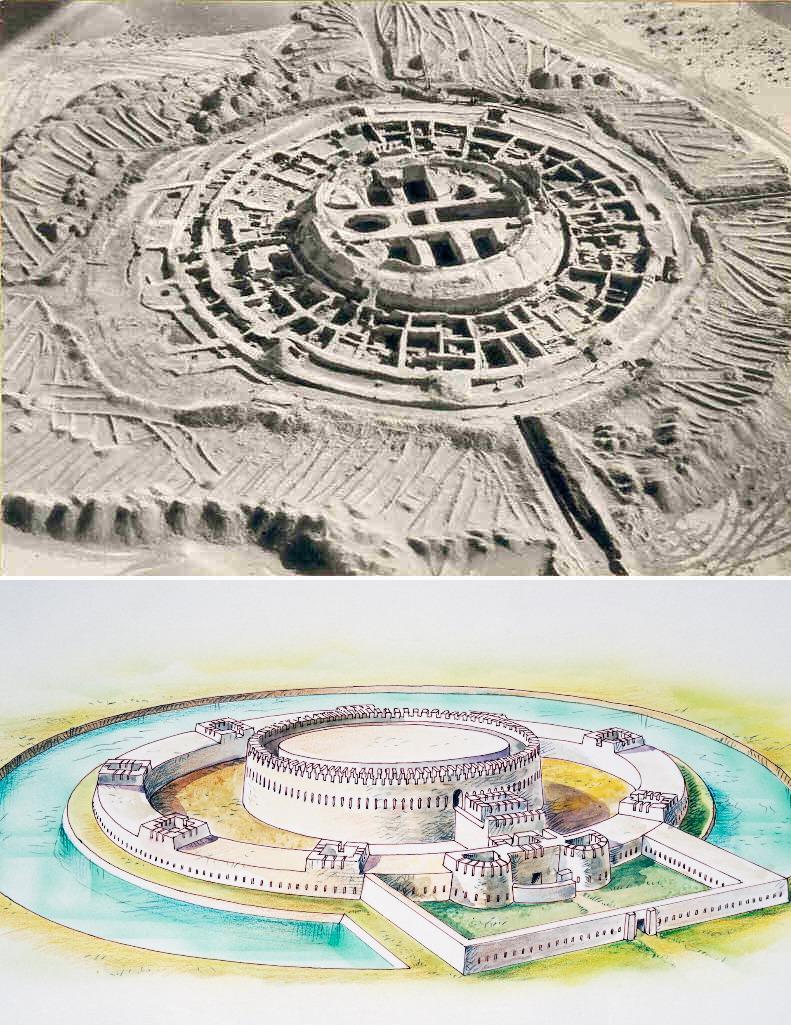

Located in the vast desert plains of Khorezm, the fortress known as “Dead Sheep” was first discovered in 1938 by chance. Its unusual architecture, particularly its perfectly circular design, quickly drew the attention of researchers. The fortress featured a powerful defensive infrastructure and was surrounded by thick brick walls and multiple towers forming an additional protective ring. Between the central fortress and the outer wall, archaeologists uncovered remnants of domestic structures and everyday household items, indicating the area was actively inhabited.

The structure itself is impressive in scale: the inner fortress had a diameter of over 40 meters, with walls reaching heights of up to eight meters based on current archaeological evidence. The entire complex spanned nearly 90 meters in diameter.

Excavations have yielded a wealth of archaeological artifacts, including clay pottery, bronze arrowheads, decorative ornaments, and the remains of defensive structures. Some of the earliest items found at the site date as far back as the fourth millennium BC.

The fortress underwent multiple stages of development. The earliest phase, from the fourth to third century BC, shows evidence of a devastating fire, though the cause remains unknown. A central phase followed in the second century AD, marking continued use and reconstruction.

Historically, the “Dead Sheep” fortress served multiple roles in ancient Khorezm. It was not only a major temple complex but also closely tied to the political formation of the ancient city-state. Notably, the remains of the city’s rulers were buried within the fortress grounds.

Over the centuries, the site has witnessed both triumphs and tragedies. It has yielded a variety of artifacts from different periods, including murals, religious buildings, weapons, and household goods. Ethnographic studies revealed that the inhabitants practiced Zoroastrianism, worshipping deities associated with natural elements—Siyavush, the god of the sun, and Anahita, the goddess of water.

Architecturally, the spatial layout of the complex reflects these beliefs. The western section was dedicated to Anahita, while the southern and eastern areas honored Siyavush. This is supported by the discovery of sacred statues, ceremonial vessels, and other religious objects throughout the site.